John Peter Zenger was arrested on a Sunday in November 1734, on charges of libel.

The warrant for his arrest read, in part:

"… his Journals or News Papers… having in them many Things, tending to raise Factions and Tumults, among the People of this Province, inflaming their Minds with Contempt of His Majesty's Government, and greatly disturbing the Peace thereof…"

Portrait of William Cosby, National Gallery of Ireland, Charles Jervas

Zenger, a poor German immigrant with a large family to support, had taken work publishing columns and letters in a brand-new paper, “The New York Weekly Journal”. The paper that pre-existed it was run by a man who wouldn’t publish anything critical of the colonial government. Zenger’s paper quickly became a popular outlet for people tired of the actions of the government, particularly the newest governor of New York, William Cosby.

And people had a lot of complaints about Cosby. The first thing he did on arriving at his new post was to start a fight about the size of his salary. He gained favor with the General Assembly by refusing to call for new elections. He seized the lands of some of the colonists he governed. He made promises he never intended to keep, and acted with impunity.

The seventh volume of the New York Weekly Journal

After Zenger’s arrest on charges of libel, he was not allowed to communicate with anyone for several days. The following Monday’s edition of the “Journal” never ran. After his first hearing, things changed slightly for the better. The next edition of Zenger’s paper was published, and had a message from him, that read in part:

“…I have since that time [of the hearing] the Liberty of Speaking through the Hole of the Door, to my Wife and Servants by which I doubt not yo’l think me sufficiently Excused for not sending my last weeks Journall, and I hope for the future Liberty of Speaking to my servants thro’ the Hole of the Door of the Prison, to entertain you with my weokly Journall as formerly. And am your obliged Humble Servant.”

Zenger’s bail had been set at 400 pounds sterling. In 2022 dollars, that’s about $110,000. The judge, who had been installed by the governor, also required Zenger to have two sureties, or guarantors of the bail. Zenger likely didn’t have a tenth of that sum, and people don’t leap out of walls to support those incarcerated by corrupt governments. He was going to be staying in jail for a while.

In fact, he remained there until Jan. 5 of the next year. It was then he went before a jury with hopes of being released, but was instead charged with more crimes and returned to his imprisonment.

James Alexander, via Wikimedia.

In April, Zenger’s attorneys James Alexander and William Smith made a motion before the court to seek legal relief. Not being able to match the wit of the two lawyers, the Chief Justice replied, “…you have brought it to that Point, That either, We must go from the Bench or you from the Barr: Therefore We exclude you and Mr. Alexander from the Barr.”

The judges summarily disbarred the two attorneys, with little recourse, from their entire practice in court. They were out of business. The two petitioned to be restored, but in the meanwhile, Zenger’s trial moved forward. His new, court-appointed lawyer entered a plea of not guilty but was careful not to repeat Alexander and Smith’s arguments. He had been befriended by the governor previously and didn’t want to lose his career as Alexander and Smith had.

Alexander and Smith weren’t done with the case, though. For their own sake and Zenger’s, they looked for other attorneys to take up the case on their behalf, and found Andrew Hamilton.

Hamilton, later referred to as “the day star of the American Revolution” was almost sixty years old at a time when the average life expectancy was in the mid-thirties. He took up the case on a pro bono basis and traveled to New York from Philadelphia.

He would argue that truth is a defense against charges of libel.

Andrew Hamilton made an entrance at John Peter Zenger’s trial.

The courtroom was crowded with people who saw the case as a bellwether of colonial liberty. Zenger’s press had continued to run in his absence, published by his wife, Anna Catharina Zenger, the first woman to publish a newspaper in America. The newspaper generated a lot of public support for Zenger.

The jury’s decision would either be the nail in the coffin, or an affirmation, of colonists’ rights to criticize and protest the government in the public press.

So the crowd had gathered, and very few of those in attendance had been told that Hamilton had been retained for Zenger’s defense. The judges and attorney general, inexperienced in comparison to the venerated Hamilton, were no doubt dismayed by his sudden appearance. While they had handily disbarred Zenger’s previous attorneys, they dared not do so with the well-known and highly-regarded Hamilton.

After the charges against Zenger were read, Hamilton surprised the prosecuting attorney by confessing that Zenger both printed and published the newspapers that contained the libel in question. There would be no need for his witnesses on that matter.

Then, the prosecutor asserted that since the question of who printed the newspapers had been settled, the jury must find Zenger guilty, as the truth of the words was irrelevant. In fact, he claimed, if they were true, that made the crime even worse.

However, Hamilton rebutted, “… I hope it is not our bare Printing and Publishing a Paper, that will make it a Libel: You will have something more to do before you make my Client a Libeller; for the Words themselves must be libelous — that is, false, scandalous, and seditious — or else we are not guilty.”

The prosecutor argued that the written words were a malicious attack on the character of a government official and that care had to be taken to prevent such attacks to maintain public peace. He also quoted Acts 23:5 and 2 Peter 2:10 to support his argument that any negative speech about a government official is immoral and libelous.

“May it please Your Honour,” Hamilton began to rebut, “I agree with Mr. Attorney, that Government is a sacred Thing, but I differ very widely from him when he would insinuate, that the just Complaints of a Number of Men, who suffer under a bad Administration, is libeling that Administration.”

Hamilton pressed the prosecutor and the court that for something to be libel, it must be proven false. The prosecuting attorney, however, reasserted that the truth of the libel is immaterial, and declined to endeavor to disprove the assertions.

Hamilton accepted the prosecutor’s refusal and instead moved to prove the supposed libel true, but the chief justice stopped him.

“The Law is clear,” the judge said. “That you cannot justify a Libel.”

Much of the prosecution’s arguments and judge’s decisions rested on judgments made within the highly unpopular Star Chamber. This was a court in England that had been given extraordinary powers to deal with special cases where the law wasn’t clear, or when a powerful noble was involved. However, over the course of centuries, it became synonymous with abuse of power and harsh sentencing, like branding and other bodily mutilation. The Star Chamber was abolished by the Habeas Corpus Act of 1640, but its rulings were still used to justify some legal arguments.

Hamilton made public note of this, but the judges didn’t back down.

So Hamilton was facing a hostile judge who would not let him enter evidence to establish the truth of the statements Zenger had published. It left him really one option, but one which Hamilton was well-suited for. He appealed directly to the jury.

“I pray, what Redress is to be expected for an honest Man,

who makes his Complaint against a Governour to

an Assembly who may properly enough be said, to be made

by the same Governour against whom the Complaint is made?

The Thing answers it self.

No, it is natural, it is a Priviledge, I will go farther,

it is a Right which all Freemen claim,

and are entitled to complain when they are hurt;

they have a Right pulbickly to remonstrate the Abuses of Power,

in the strongest Terms, to put their Neighbours upon their Guard,

against the Craft or open Violence of Men in Authority,

and to assert with Courage the Sense they have of the Blessings of Liberty,

the Value they put upon it, and their Resolution at all Hazards to preserve it,

as one of the greatest Blessings Heaven can bestow.”

Hamilton spoke eloquently and at length, establishing the rightfulness and necessity of a people to be able to publicly criticize their government, of the danger of “Mr. Attorney’s” definition of libel, and of a jury’s duty to decide not only the facts but the law.

This last point also displeased the Chief Justice, who, like the Star Chamber judges before him, had hoped to dictate to the jury what their decision should be.

The jury left to deliberate but returned very quickly. They unanimously found Zenger to be not guilty. The assembled crowd gave three cheers in response.

The right of the people to speak freely in the press was established for the first time. They had the right to criticize the people in power without fear of imprisonment, and they would use that right in the not-so-distant future. The newspapers to come would help fuel the American Revolution.

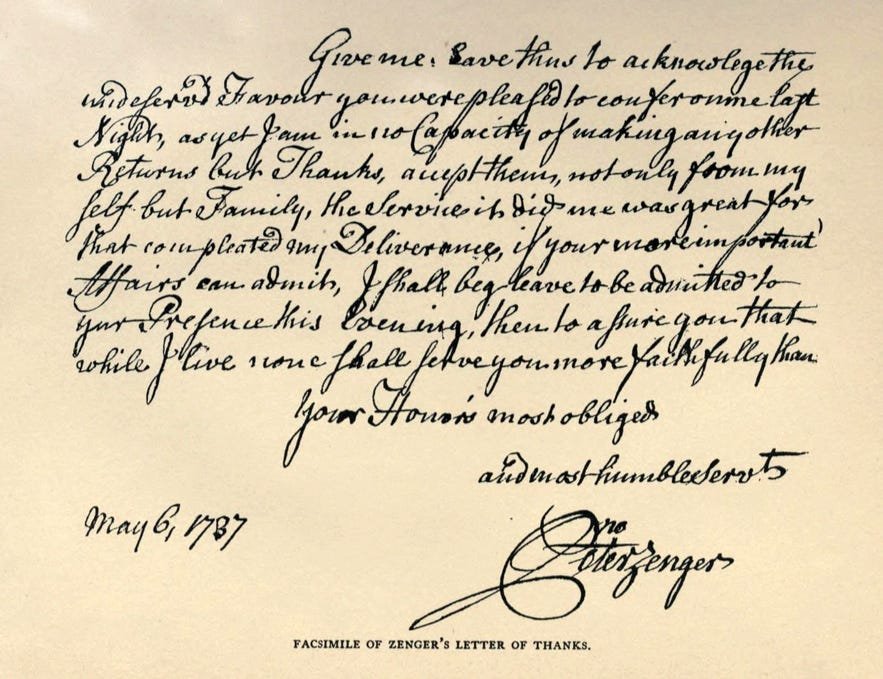

Letter of thanks from Zenger to Hamilton